I was drawn to The Last Stand: Custer, Sitting Bull and the

Battle of the Little Bighorn not so much by its subject matter, but by its

author, Nathaniel Philbrick.

For one thing, I was intrigued as to why a writer who

heretofore had written about the sea and coastal areas, and had done so in

admirable fashion, would venture into the hinterland and write about two of the

icons of the American West and one of the most famous battles in American

history.

I wasn’t sure that it would be possible to learn anything new since

there have been dozens of books written about the subject he had chosen.

Philbrick indicates that his first real introduction to Custer was in the film LITTLE BIG MAN (National General) released in 1970, and that it sparked his interest in the subject. I would say that his introduction was a poor one.

Philbrick indicates that his first real introduction to Custer was in the film LITTLE BIG MAN (National General) released in 1970, and that it sparked his interest in the subject. I would say that his introduction was a poor one.

Although I like Thomas

Berger’s novel upon which the film is based, I never liked the film. It seems

to me that the filmmakers could never make up their minds if they were making a

satire, a comedy, or a dramatic film. And Richard Mulligan’s portrayal of

Custer as a psychotic and hysterical coward is over the top and way off the

mark.

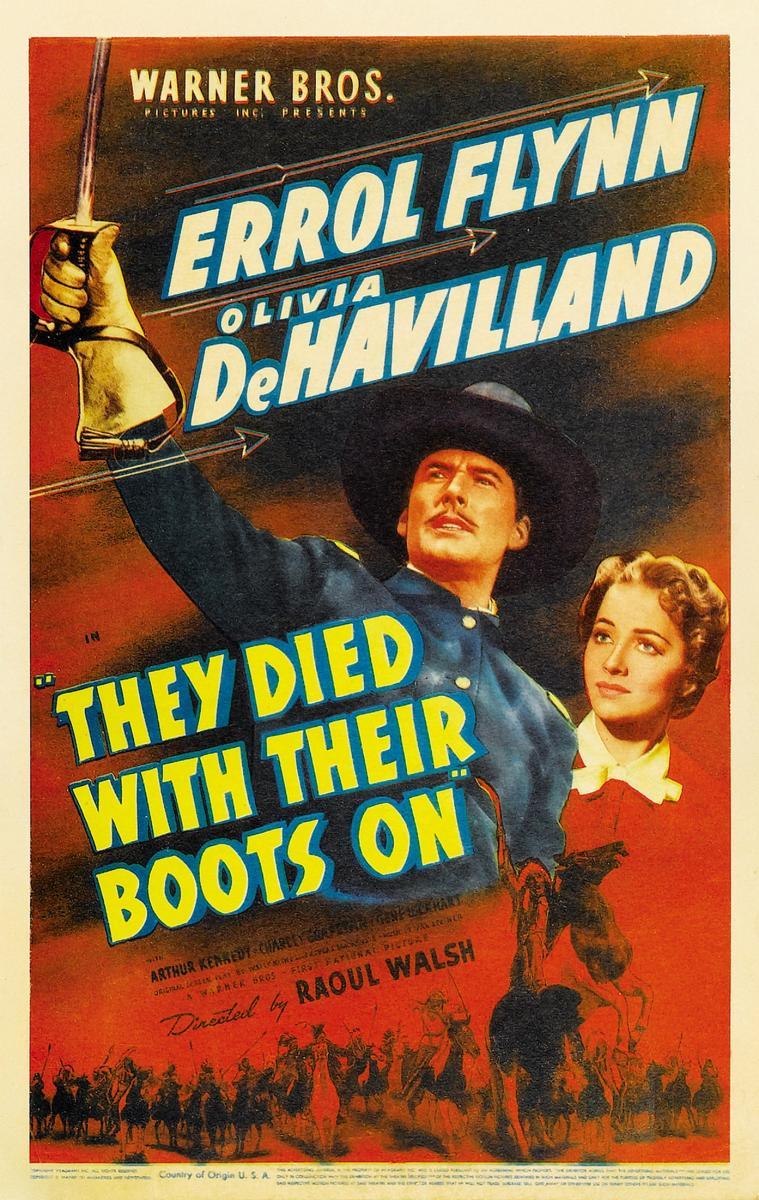

My own introduction to Custer, on film anyway, was a black-and-white production made

by Warner Brothers and released in 1942, that I first saw on late night TV. It

was They Died With Their Boots On and starred Errol Flynn as Custer.

It was a

whitewash job as far off the mark as the 1970 film, but in the opposite

direction. But then what could you expect from Hollywood? If they were able to

make a Robin Hood out of Jesse James in 1939, making a hero out of Custer was

easy.

|

| Errol Flynn as a Custer who never was |

Neither of these Custer films were accurate portrayals, though I have to admit that I enjoy watching the earlier film a lot more than I do the later one. But the truth was located

somewhere in the middle. And that is what we get from Philbrick.

I think he was

right to spread the blame for the debacle at the Little Bighorn among Custer

and his second-in-command, Major Marcus Reno, and his senior captain, Frederick

Benteen. I did find it interesting that he did not let the overall commander of

the campaign off the hook either.

That would be General Alfred Terry, who was,

I was interested to learn, the only non-West Point general in the post-war

army. Most accounts have not had much to say about General Terry’s role in the

disaster and when they do they generally find no fault in his leadership.

If you are a student of the battle and its principals or if you have visited the battlefield as I have on three occasions (the most recent being last summer) then you probably are not going to learn a lot of new information. If, on the other hand, you haven’t immersed yourself in the subject but are interested and would like to learn more about the most disastrous military defeat in U.S. history, this book would be a great place to start.

If you are a student of the battle and its principals or if you have visited the battlefield as I have on three occasions (the most recent being last summer) then you probably are not going to learn a lot of new information. If, on the other hand, you haven’t immersed yourself in the subject but are interested and would like to learn more about the most disastrous military defeat in U.S. history, this book would be a great place to start.

I would also recommend Son of the Morning Star by Evan Connell, which was

written about twenty-five years ago. Connell is a novelist and though the book

is non-fiction it reads like a good novel, but it is also historically

accurate. And I have on my “to read” list yet another recent Custer book that

is receiving good reviews, A Terrible Glory by James Donovan.

No comments:

Post a Comment