"What

William Faulkner implies, Erskine Caldwell records." -- Chicago Tribune

"Caldwell

writes with a full-blooded gutsy vitality that makes him akin to the truly

great." -- San Francisco Chronicle

At

one time, and maybe even today, God's

Little Acre (1932) was the most popular novel ever published, selling a

reported fourteen million copies. But in

the process, the book ignited a firestorm of controversy, leading to numerous

efforts to suppress it.

A

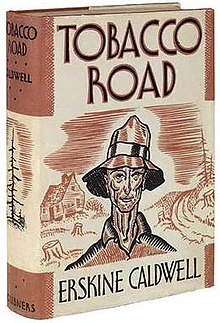

year earlier, Caldwell's Tobacco Road

was published. It had become a runaway

best-seller after it was adapted as a stage play. When the play ended its long run years later,

it was the longest-running play in Broadway's history. The play spurred book sales and eventually

ten million copies were sold.

Caldwell's

portrayal of poor white southern tenant farmers who had been exploited by their

landlords outraged many southerners and received mixed reviews from

critics. There were also charges that its

explicit sexual scenes constituted obscenity and it was banned from many

libraries, including in his hometown, and efforts were made to suppress it

elsewhere.

That

was only the beginning. God's Little Acre was even more

controversial.

Once

again Caldwell wrote about the dire straits of poor white rural people who when

faced with choices rarely chose the right one.

But it also focuses on southern textile mill hands who are exploited by

their employers. At one plant the

workers strike for higher wages and a shorter work week, but because they are deprived

of union protection the owners lock them out and shut down the mill.

There

is no doubt that Caldwell was influenced by several strikes by southern textile

workers that occurred in the late '20's and early '30's, strikes that were in

response to the fact that they were the lowest paid textile workers in the

nation.

While

Caldwell again presented his story as a curious combination of black humor and

tragedy, a combination that confuses critics -- not to mention readers -- God's Little Acre becomes very serious

-- deadly serious -- when it turned from the humorous efforts of Ty Ty Walden

and his sons to find gold on their farm to an attempt by Ty Ty's son-in-law to

forcibly re-open the textile plant that has kept him and his co-workers

unemployed for a year and a half.

The

sexual scenes in God's Little Acre are even more explicit than in Tobacco

Road. And while they are relatively

mild by today's standards, they were not mild by the standards of that day.

In

1933, Caldwell and his publisher, Viking Press, were hauled into court on a

charge of disseminating pornography. It

was reported that more than sixty writers, editors, and literary critics

rallied to his support. Caldwell's

defense was that if his book was obscene it was because the truth was

obscene. The judge ruled in his favor,

declaring that the book was literature and not pornography. However, that did not deter other efforts to

suppress the book. But what would-be

book banners never seem to learn is that all that publicity spurs sales and the

novel became not only Caldwell's biggest seller, but one of the biggest ever.

The

book was still very controversial many, many years later and that is why I

tucked my copy inside my lit book during my sophomore year in high school. I knew that it was going to be a lot more

interesting than my assigned reading.

Well, I must confess that it wasn't just the controversy. It was also the lurid cover featuring a

scantily-clad, well-endowed young lady on the cover of the paperback re-issue

that I possessed. But that's another

story.

You

probably already know the meaning of the book's title by now, but if not, I

don't wish to be a spoiler. I'll let the

publisher's blurb describing the book do that.