You can read Randolph Scott: The Paramount Years, 1932-1938 here.

You can read Randolph Scott: Western Star, 1938-1945 here.

1946 was a pivotal year for Randolph Scott. At the mid-point of his career the actor had risen from the ranks of bit player to leading man. Over the years he had alternated between Western and non-Western roles (including five military pictures during the war years) and a memorable performance as a William S. Hart-like "good badman" in WESTERN UNION (Fox, 1941) that resulted in him stealing the picture from its putative star, Robert Young. In the coming years, with a couple of exceptions, he would not ride the good badman trail, but he would often portray a character seeking revenge who did not hesitate to take the law into his own hands.

Approaching fifty, Scott, still tall and lanky with features becoming more weathered and rough-hewn, looked more and more like an authentic westerner. Then there was the voice. His southern accent lent an air of authenticity to his characterizations, for many a southerner, looking to escape the economic ruin of the post-Civil War South had heeded Horace Greeley's advice and gone West. It was easy to believe that the characters portrayed by Scott had been among those who had traveled westward in search of a new beginning.

.jpg) |

| Randy gets the drop on the always menacing Jack Lambert in ABILENE TOWN |

But in 1946, the actor reached a major turning point in his career. It occurred when he starred in two more medium-budget Westerns: ABILENE TOWN (UA, directed by Edwin L. Marin) and BADMAN'S TERRITORY (RKO, directed by Tim Whelan). After these two, Scott, with only three exceptions, devoted his remaining career to making Westerns. In the years from 1946 to 1956, he starred in thirty-one Westerns. It is significant that those films fell into the medium-budget category. It is true that some of them were no better than routine, but most were above average, and at least three were truly outstanding. But no matter the quality of the film, there was one constant that the viewer could depend on: Randolph Scott. He gave every film his best effort and he was always good -- and on a few occasions even better than good.

ABILENE TOWN, based on an Ernest Haycox (one of the greatest of all Western novelists) story contained all the elements of a traditional Western and, in fact, combined a number of concurrent themes that are ordinarily dealt with on a separate basis in most Westerns. Scott portrayed town marshal Dan Mitchell, who must contend with conflicts between his town and the cowmen -- between cowmen and homesteaders -- and between the town merchants and the marshal himself, since it would harm their business if he puts too tight a rein on the cowmen.

If that isn't enough to occupy the lawman's time he must also oppose a crooked saloon owner (weren't they all?) who wants a wide-open town.

The film is unnecessarily slowed by too many pauses for musical interludes by saloon girl, Ann Dvorak. However, the presence of the beautiful Rhonda Fleming was an asset. The same could be said for Edgar Buchanan (except for the beautiful part), who, as a cowardly sheriff, provides a light touch that is easy to take.

BADMAN'S TERRITORY was indicative of what had happened to the outlaw biography trend in Westerns. Beginning with JESSE JAMES (Fox) in 1939, all the major outlaws had had their biographies filmed by 1946, therefore in order to be different BADMAN'S TERRITORY pitted practically every outlaw in the West (the James brothers, Belle Starr, the Dalton brothers, the Younger brothers, Sam Bass) against lawman Scott. A similar thing occurred two years later in RETURN OF THE BADMEN (RKO), when Scott took on the Sundance Kid (Robert Ryan), who had united a band of badmen that included the Daltons, Youngers, and Billy the Kid (I don't know how the Kid missed being in the earlier film.).

Both RKO productions appealed to both "A" and "B" Western devotees; they were fast-paced oaters with many of the elements of the B-Western and the cast included actors that were familiar to B-Western audiences, including long time B-Western sidekick, Gabby Hayes, who appeared in both, but the films were also characterized by bigger budgets and longer running times than the more modest "B's". Included in the casts were Tom Tyler, Robert Ryan, Anne Jeffreys, Tom Keene, Steve Brodie, James Warren, Chief Thundercloud, Kermit Maynard, and Lane Chandler. Several of the actors appeared in both films.

|

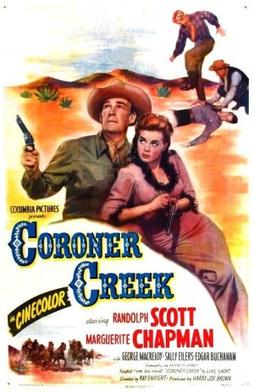

| See the scene depicted in the upper right hand corner? The viewers did not see it in the film, for it occurred off-camera. |

In 1948, after a number of so-so movies, Scott hit the jackpot with CORONER CREEK (Columbia). Based on a solid Luke Short novel, it is one of the three best Scott Westerns produced between WESTERN UNION in 1941 and the Scott-Boetticher-Brown films of the '50's. In many respects, primarily because of its revenge motif (Scott searches for the murderer of his wife), the solid Western was a precursor of those films.

There are also two rather brutal scenes in the film. In the first, Forrest Tucker, after a lengthy fistfight with Scott, drags him into a creek and then proceeds to stretch Scott's gun hand across a rock and crushes it with his boot heel.

When, as a youngster, I first saw this film I thought the scene was more explicit than it actually was. I recalled that when Tucker stamped on Scott's fingers that there was a close up of boot on fingers. I later realize that I thought this because I apparently looked away at the last moment, unable to view the horror that was occurring. After viewing the film many years later, I discovered that the camera had cut away at the last instant and that the violence had not been as graphic as I had assumed. Evidently, my mind's eye had completed the scene for me.

The second brutal scene is a reversal of the first. Scott ruins Tucker's gun hand in the same manner. And again I would have sworn that I saw Scott's boot crush Tucker's hand, but I didn't.

|

| Two big men who were always believable in badman roles; (L-R) Forrest Tucker and Bruce Cabot, in a scene from the Randolph Scott film GUNFIGHTERS (Columbia, 1947). Tucker played a prominent role in several Scott films and the two (and their stunt doubles) often engaged in brutal fisticuffs. |

Scott receives a lot of good support in CORONER CREEK from Marguerite Chapman, George Macready (always a chilling presence on the screen), Forrest Tucker (a welcome presence in Westerns, especially those starring Scott), and Edgar Buchanan and Wallace Ford (two old-timers who always added to the enjoyment of the films they appeared in).

|

| In this scene it appears that Scott is left handed. But note his bandaged right hand. This scene with Edgar Buchanan and William Bishop occurred after Scott's brutal fight with Forrest Tucker. |

In 1949, Scott formed separate production units with Nat Holt and Harry Joe Brown. While his association with Holt (just three films) failed to produce the hoped for results, his partnership with Harry Joe Brown would be an extremely happy one and would result in the production of some highly enjoyable Westerns.

Brown's career in Western film making extended all the way back to the silent days when he had been in charge of an outstanding series of First National B-Westerns that had propelled Ken Maynard to stardom. Brown also directed several of Maynard's early sound Westerns at Universal. He also produced a number of Scott films before the two formed their production company.

Scott and Brown began their partnership with THE NEVADAN (Columbia, 1950, directed by Gordon Douglas). The film is not one of the team's better efforts, but it is noteworthy for a solid supporting performance by Forrest Tucker and great stunt work by the incomparable Jock Mahoney, who also has a featured supporting role as a villain. Dorothy Malone provides romantic interest while George Macready is the boss villain.

As mentioned earlier, CORONER CREEK was the first of the three best Scott films during the era being discussed; the second is THE WALKING HILLS (Columbia, 1949).

|

| Randolph Scott, William Bishop, and Ella Raines in THE WALKING HILLS (Columbia, 1949) |

Unappreciated at the time of its release, the noirsh Western is set in the modern West, and covers some of the same ground as THE TREASURE OF THE SIERRA MADRE (WB), which was released a year earlier. Allan Le May's screenplay revolves around the efforts of an unsavory group of characters who band together in an effort to find a long-lost wagon train. Reportedly transporting gold, it had disappeared a hundred years earlier and had been buried in the windblown sand dunes of Death Valley.Directed by John Sturges (the first of his many good Westerns), the film sported a strong supporting cast that included the beautiful and fiery Ella Raines, William Bishop, Edgar Buchanan, Arthur Kennedy, Jerome Courtland, Josh White, and John Ireland. Always capable of giving an interesting performance when direction and screenplay allowed it, Ireland is especially effective as the most disreputable of the disreputable entourage.

The other outstanding Scott film during this stage of his career is MAN IN THE SADDLE, based on a superior Ernest Haycox novel. Besides being an excellent range war film, it is sometimes singled out for special recognition due to Tennessee Ernie Ford singing the title song over the credits (and in one campfire scene). This occurred a year before Tex Ritter did the same in the more highly acclaimed HIGH NOON (UA, 1952).

The night time photography provided by Charles Lawton, Jr. is superb and the extended brawl between Scott and John Russell rivals those engaged in by Scott and Forrest Tucker. In fact, Scott and Russell's slugfest is so violent that the cabin in which they are fighting is so completely demolished that the walls and the roof collapse.

It is one of de Toth's most entertaining Westerns and is easily the best of several Scott-de Toth collaborations. Alexander Knox, Joan Leslie, Ellen Drew, "Big Boy" Williams, Alfonso Bedoya, Cameron Mitchell, Clem Bevans, along with John Russell, round out a solid cast.

|

| Two tough hombres. |

|

| HANGMAN'S KNOT (Columbia, 1952); Scott wears the worn leather jacket that had become a trademark in his later films.

HANGMAN'S KNOT (Columbia, 1952) is not quite on a par with CORONER CREEK, THE WALKING HILLS, or MAN IN THE SADDLE, but it is a cut above the actor's other films of that period. The supporting cast features Donna Reed, Richard Denning, Claude Jarman, Jr., Frank Faylen, Ray Teal, and "Big-Boy" Williams. It was interesting to see Williams, usually a Scott compatriot, as one of the ornery leaders of an ornery posse laying siege to Scott and his gang who have taken refuge in a remote stage relay station. However, the most interesting performance in the film is by a young unknown actor by the name of Lee Marvin, who would soon come into his own as one of Hollywood's most dependable character actors. Although he is a member of Scott's gang it is apparent from the beginning that their antagonistic relationship would have to be reconciled in one way or the other.

It is also the only film directed by Roy Huggins (who also wrote the screenplay), who later achieved fame as the creator of the Maverick and Rockford Files TV series.

With its isolated locale and its emphasis on characterization, and the strong performances of Scott and his supporting cast, the film reminds one of Scott and Boetticher's RIDE LONESOME (Columbia, 1959) and COMANCHE STATION (Columbia, 1960).

But that's a story for another day. TO BE CONTINUED ---- |

No comments:

Post a Comment