Serials, sometimes called chapter plays or cliffhangers, were an early staple of movie production, even during the silent era. And from the beginning, many of them were set in the Old West. Later it was inevitable that the producers of serials, targeted as they were toward a juvenile audience, would also look to comic strips for source material. It wasn't long before various studios began to churn out serials starring the likes of Flash Gordon, Buck Rogers, Dick Tracy, Mandrake the Magician, and others.

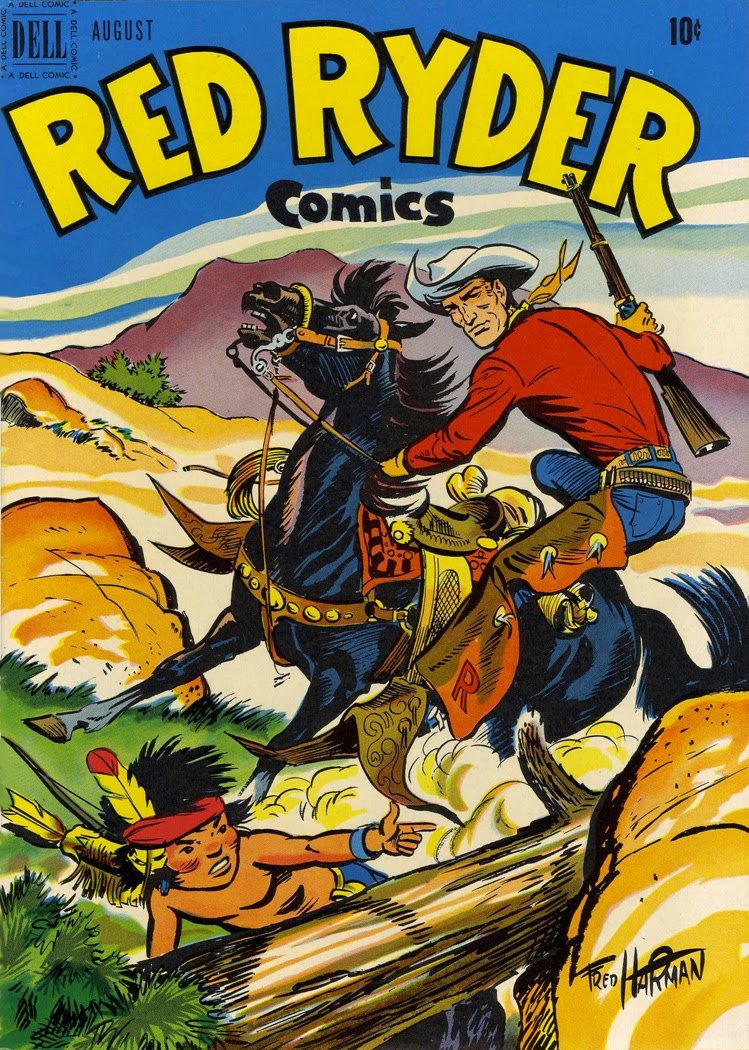

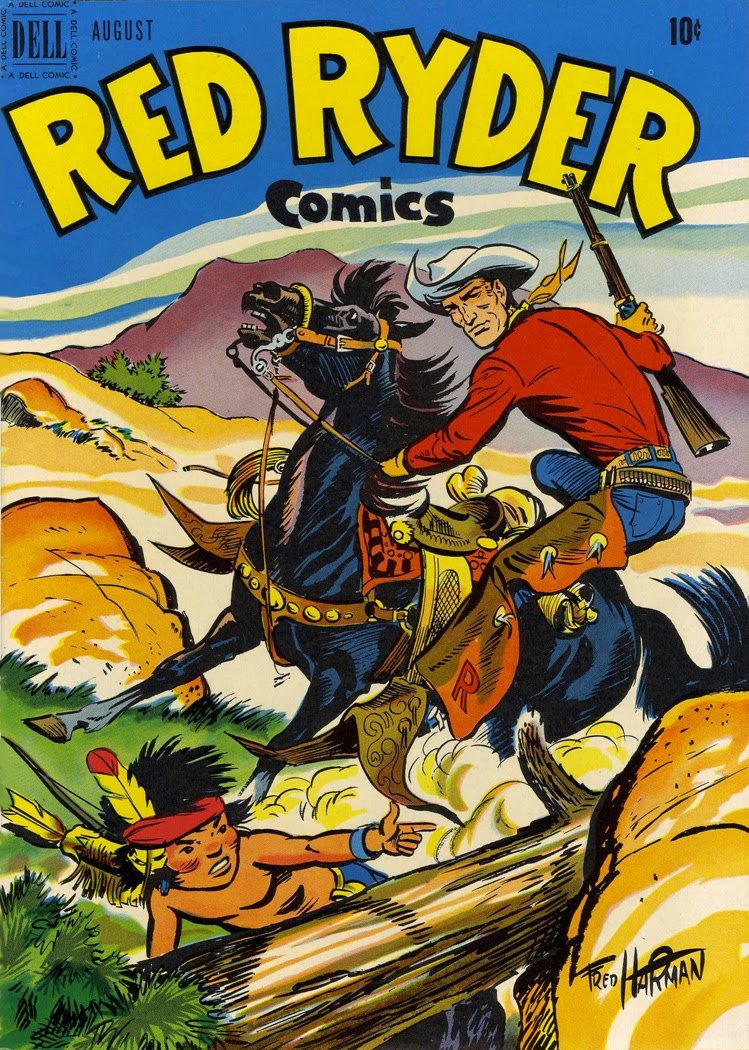

Since studios were looking for both comic strip heroes and Western settings as inspirations for their serials, it was only a matter of time before Red Ryder appeared on the big screen. Created by Fred Harman, the strip had been an immediate hit when it debuted in 1938. Two years later, Republic released ADVENTURES OF RED RYDER as a 12-chapter serial.

DIRECTORS: John English, William Witney; PRODUCER: Hiram S. Brown, Jr.; WRITERS: screenplay by Franklyn Adreon, Ronald Davidson, Norman S. Hall, Barney A. Sarecky, Sol Shor; CINEMATOGRAPHY: William Nobles

CAST: Don "Red" Barry, Noah Beery, Tommy Cook, Maude Pierce Allen, Vivian Coe, Harry Worth, Hal Taliaferro, William Farnum, Bob Kortman, Careleton Young, Ray Teal, Gene Alsace, Reed Howes, Lloyd Ingraham

STUNTS: David Sharpe (double for Don 'Red' Barry), Gene Alsace, Art Dillard, James Fawcett, Bud Geary, Duke Green, Eddie Juarequi, Ted Mapes, Post Park, Ken Terrell, Bill Yrigoyen, Joe Yrigoyen

THE PLOT.

Stop me if you have heard this one. The Santa Fe railroad is planning to run its line near the town of Mesquite. As in all such cases in the B-Western West, there are crooks that have inside information about the proposed right-of-way. They institute a reign of terror and intimidation against the local ranchers in order to grab their land and place themselves in the path of the right-of-way, which will then be purchased from them by the railroad.

In the first chapter, Col. Tom Ryder (William Farnum), father of Red, and sheriff Luke Andrews (Lloyd Ingraham), father of Red's friend Beth (Vivian Coe), decide to organize an effort to counter the terroristic activities. Both are killed by a group of henchmen headed by One-Eye Chapin (Bob Kortman).

Red (Don Barry) then becomes the leader of the fight to defeat the outlaws. In his efforts he is assisted by his juvenile Indian sidekick, Little Beaver (Tommy Cook), and a loyal ranch hand by the name of Cherokee Sims (Hal Taliaferro). He is also supported by his aunt, the Duchess (Maude Pierce Allen), who is in jeopardy of losing her own spread.

Almost from the beginning, saloon owner Ace Hanlon (Noah Beery) is suspected of being the leader of the gang. This could be because nearly all saloon owners in the B-Western West were crooks. However, what is not known is that banker Calvin Drake (Harry Worth) is the real brains behind the illegal activities. It should have been known, of course, because Drake wears an eastern suit and, especially, because he sports a thin mustache. The combination was a dead giveaway but it took Red and his allies twelve weeks to catch on. But they do, and in the end, the forces of good prevail over the forces of evil.

|

| Fred Harman's Red Ryder (and Little Beaver) |

THE STAR.

The directors were not pleased with the choice of native Texan Don Barry in the lead role. And that is putting it mildly. Here is what William Witney, one of the serial's co-directors, wrote about the casting in his memoir (In a Door, Into a Fight, Out a Door, Into a Chase):

"Jack [co-director John English], Bunny [producer Hiram Brown] and I had started to look for actors to fill out the cast. We were looking for a lean, craggy-faced western type about six-foot-six....

One morning the front office called Bunny and told him that they had solved our problem. They had cast Don Barry in the part and had just signed him to a long-term contract. None of us knew Don, so we checked him out with casting. He had been cast in small roles in a mesquiteer series picture and a couple of Roy Rogers pictures. We wanted to meet him.

After we met Don we all decided that he was too short to play the role and his brain matched his size. The only thing he had that was big was his ego....

When the picture was finished we decided not to have our usual party. The picture hadn't been pleasant. Jack and I went across the street to have a drink. At the bar Jack turned to me. 'Remember when we were wardrobing the midget and I said everything looks too big for him, and that hat he picked was ridiculous? Well, I was wrong. His head grew into the hat. God help the next poor directors who have to work with him....'"

|

| Little Beaver (Tommy Cook) rides double with Red Ryder (Don Barry) on Red's black stallion, Thunder. Unfortunately, Barry's big hat makes him seem even smaller than his actual size. Fortunately, having a sidekick of Cook's stature makes him seem larger than his actual size. |

Barry, who stood only about 5-5, got the part because he was the personal choice of the man who bossed the studio, Herbert Yates. Yates viewed the cocky, diminutive Barry as another Cagney.

William C. Cline in his account of the serial genre, In the Nick of Time, described the Barry persona in words that could have been used to describe Cagney:

"With a jaunty carriage and high-pitched husky voice that clipped out his lines in an unmistakably authoritative tone, the swaggering young hero brought to mind as much as anything else a confident, self-assured gamecock."

THE DIRECTORS, SUPPORTING CAST, AND STUNTMEN.

|

| Co-directors William Witney (L) and John English (R) flank producer Hiram Brown |

At age twenty-five, William Witney, a native of Lawton, Oklahoma, was a veteran serial director. He had been pressed into service when he was only twenty-one, when the director of the picture was fired for drunkenness. He went on to become Republic's busiest and most talented director of serials and B-Westerns. He was a director who loved to stage action scenes and he became adept at doing so. In later years, when he was put in charge of the Roy Rogers series, he eliminated as much of the music as possible and they became much more action oriented.

John English was born in England in 1903, but grew up in Canada. He became a director at Republic at about the same time as Witney. Despite the age difference, the two worked extremely well as a team and were responsible for Hollywood's very best serials, giving Republic a huge advantage over its competitors. As a team, they directed seventeen consecutive serials.

Most serial productions utilized two directors in order to expedite production. Each director was in charge of filming on alternate days. While one filmed, the other prepared for the next days filming. Witney and English were a good team because Witney did what he did best, which was staging the action scenes, while English preferred to direct the scenes involving character development and story.

Maybe Barry was too small for the part, but it is not very apparent on the screen, except when he is astride Thunder, and he was a much better actor than just about any other B-Western performer. He was a competent rider who could also handle himself in the fight scenes -- and there were many, of course, as there were in nearly all serials. Plus, his double made him look even more proficient. Maybe it is true that the directors did not like the actor and that he was hard to work with, but that doesn't show up on the screen.

Barry, for his part, had higher aspirations as an actor than starring in lowly serials or B-Westerns. He was also unhappy with the moniker that he was stuck with in his B-Westerns. Although the above poster lists his name as Donald "Red" Barry, which the actor didn't like either, his name in the opening credits in each chapter of the serial is Don "Red" Barry. And to his dismay, he would be billed as Don "Red" Barry for the remainder of his B-Western career.

The supporting cast, especially old pros such as Beery, Taliaferro, and Kortman, were important factors in explaining the success of the serial. As child actors go, Tommy Cook, who had appeared in only two short films prior to the serial, was quite good as Little Beaver. Despite the fact that he had never been on a horse, he was athletic and became quite proficient at riding after only a few lessons.

In a departure from Harman's cartoon strip (and the Red Ryder comic books, the subsequent feature movies, and the radio show), Little Beaver, for some reason, is identified as Apache rather than Navajo. Also, his pinto pony has no name, while in all the other mediums it was identified as "Papoose."

Serials above all were about action -- and more action. And that in turn meant that their success was highly dependent on stuntmen (there were practically no stuntwomen at the time) and directors who knew how to show them to their best advantage. This serial is a veritable "Who's Who" list of stunters and in Witney, they had the best director in the business to guide them. And while the director never had much good to say about the actors who starred in his serials, he admired and respected the stuntmen.

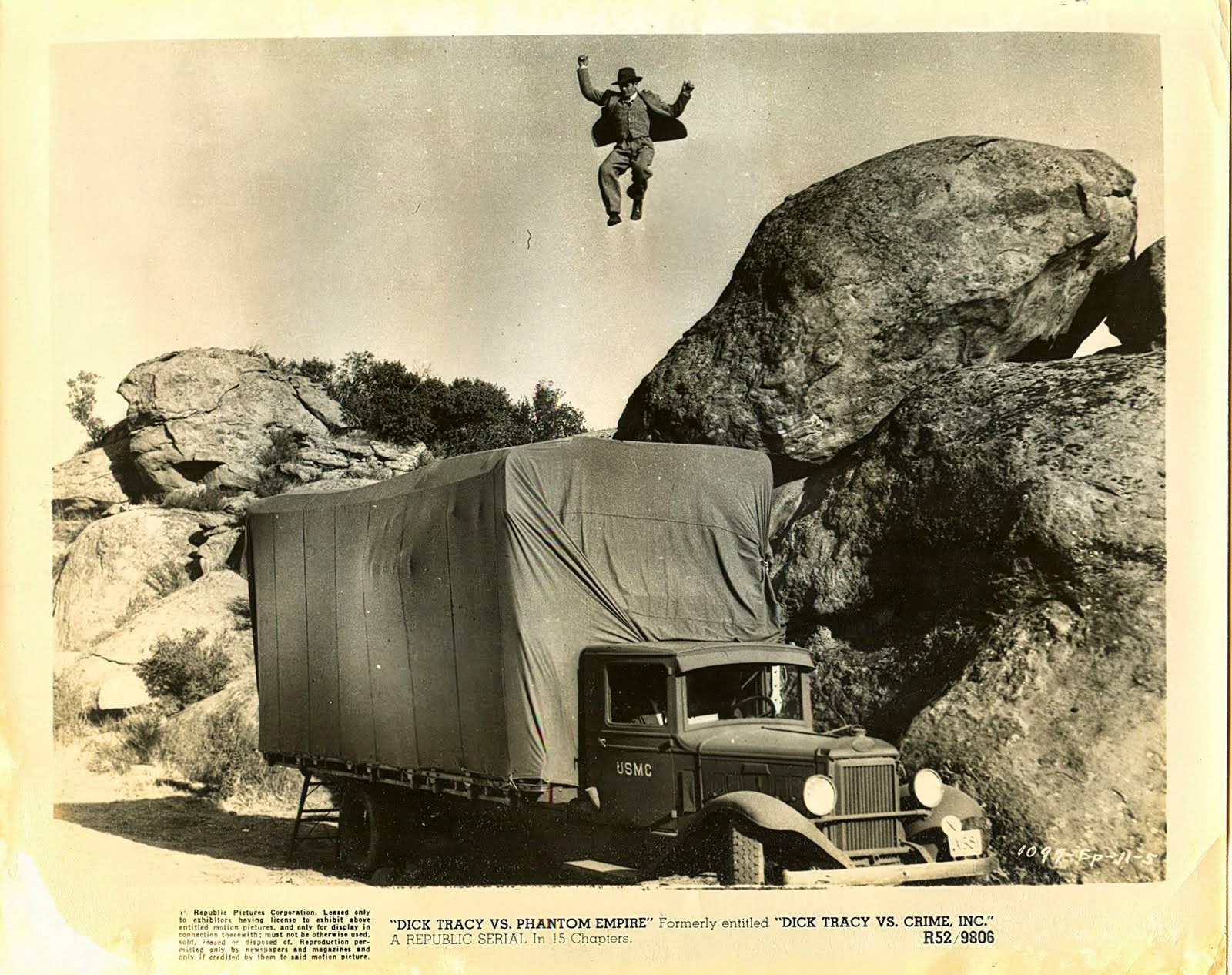

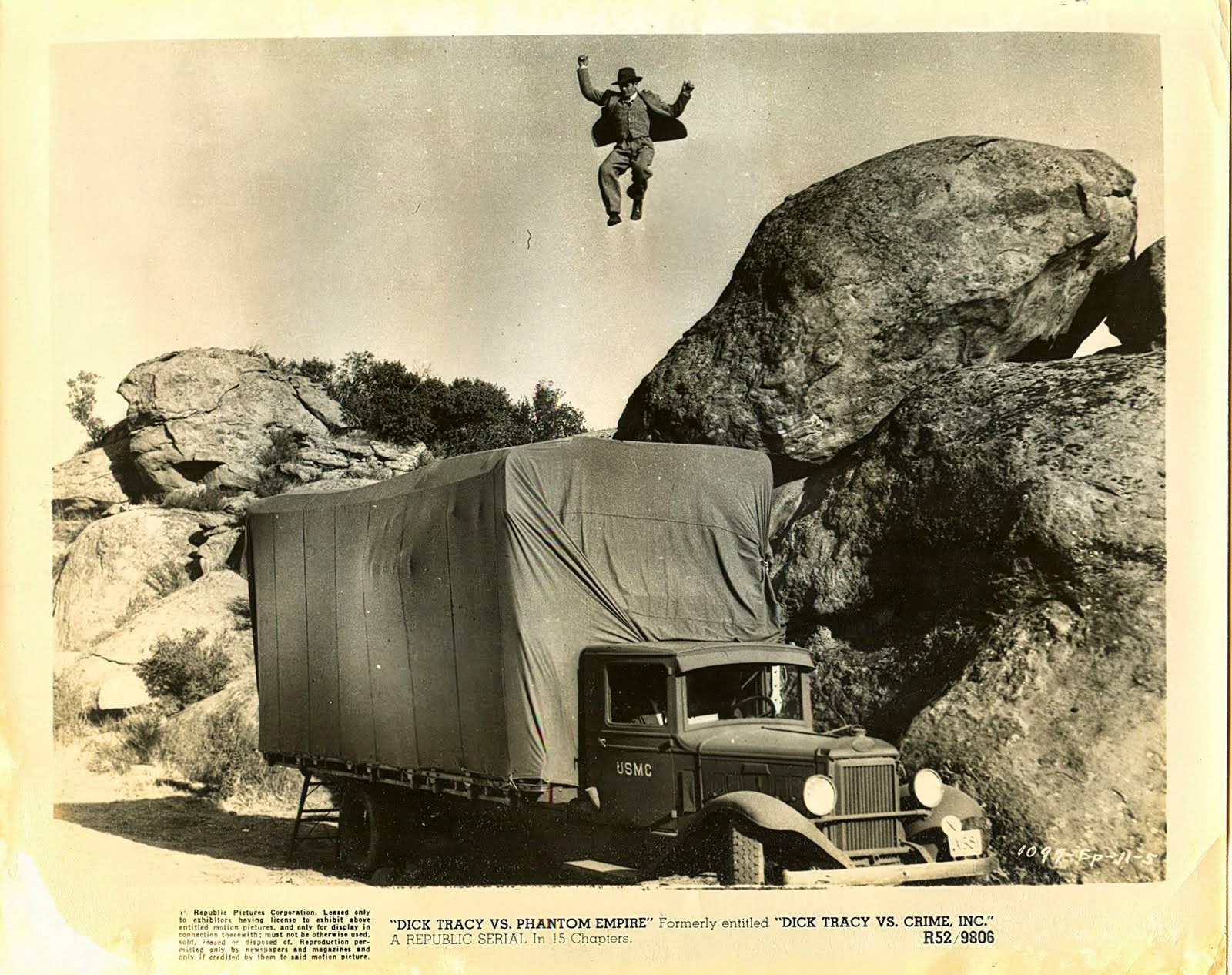

In many ways, the most important performer in the serial, even more important than its star, is the man who doubled him. David Sharpe was one of the very best in the business.

It wasn't absolutely necessary, but it was helpful that Sharpe wasn't much taller than Barry. It wasn't necessary because Sharpe often doubled actors much taller than him. His small stature also allowed him to double women at a time in which, as mentioned, there were few stuntwomen in the business.

Sharpe was an acrobat who had been a champion tumbler. He could ride and fight and he could perform stunts that nobody else could. Early in the serial he reprises the old Yakima Canutt stunt of falling from the tongue of a stagecoach, allowing the coach to pass over him, then grabbing the under carriage and pulling himself back onto the coach, at which point he proceeds to best a young Ray Teal in a battle of fisticuffs. It was all in a day's work for Sharpe -- and Witney.

|

| Davey Sharpe, legendary stuntman |

|

| Davey Sharpe leaping onto a moving truck, while doubling for Ralph Byrd in one of the Dick Tracy serials. |

In 1968, he began a long tenure on the University of Florida faculty. Woo

writes that "during his three decades there, he swore, drank and

generally fractured the academic mold. With piercing blue eyes set deep in his

craggy face, a limp caused by one or another violent encounter, a wardrobe that

ran to sleeveless T-shirts and denims, and an assortment of tattoos (including

one of a skull with a line from ee cummings, how do you like your blue-eyed

boy/Mister Death’), he looked like the type

of person one would cross the street to avoid meeting.

In 1968, he began a long tenure on the University of Florida faculty. Woo

writes that "during his three decades there, he swore, drank and

generally fractured the academic mold. With piercing blue eyes set deep in his

craggy face, a limp caused by one or another violent encounter, a wardrobe that

ran to sleeveless T-shirts and denims, and an assortment of tattoos (including

one of a skull with a line from ee cummings, how do you like your blue-eyed

boy/Mister Death’), he looked like the type

of person one would cross the street to avoid meeting. I have read most of his novels and

though I have to admit that they are not among my favorites, I will always have

vivid memories of each of them, for they are impossible to forget. How could I

forget a story about a man who sets out to eat an entire car, a Ford Maverick,

piece-by-piece (Car, 1972), or a

man who makes a living by knocking himself out (The Knockout Artist,

1988)?

I have read most of his novels and

though I have to admit that they are not among my favorites, I will always have

vivid memories of each of them, for they are impossible to forget. How could I

forget a story about a man who sets out to eat an entire car, a Ford Maverick,

piece-by-piece (Car, 1972), or a

man who makes a living by knocking himself out (The Knockout Artist,

1988)?